The disappearing flavor in your grandmother’s recipes isn’t a figment of your imagination; it’s a verifiable result of decades of change in the material science of our food.

- Modern ingredients like shortening and mass-market produce are fundamentally different at a molecular level from their vintage counterparts (lard, heirloom vegetables).

- Legacy cooking tools and methods, such as seasoned cast iron and conventional ovens, create chemical reactions and heat profiles that modern equipment fails to replicate without adjustment.

Recommendation: To resurrect those lost flavors, you must become a culinary anthropologist—focusing on ingredient integrity and understanding the scientific ‘why’ behind the old ways, not just the ‘how’.

There is a unique frustration that haunts the modern home cook: the inability to replicate a treasured family recipe. You follow your grandmother’s handwritten instructions to the letter, sourcing ingredients with care, yet the final dish—be it a pie crust, a stew, or a simple Sunday roast—lacks a certain soul. The flavor is close, but the magic is gone. The common explanation is a simple, almost dismissive one: nostalgia. We are told that our memory has embellished the taste, and that we are chasing a sensory ghost that never truly existed. But this explanation is often incomplete and unsatisfying.

While sensory memory certainly plays a role, it is not the whole story. The truth is often more tangible and, thankfully, more fixable. The ingredients we use today are not the same. The fats, the produce, and even the flour have undergone a significant “flavor drift” over the past 50 to 70 years. Likewise, the tools and technology in our kitchens operate on entirely different principles than the ones our grandparents used. The disconnect is not in your memory; it’s in the material science of your kitchen.

This guide takes a different approach. We will act as culinary anthropologists, digging beyond the simple instructions to uncover the hidden science behind vintage recipes. Instead of blaming nostalgia, we will explore the tangible, molecular-level differences between then and now. By understanding the ‘why’—why lard creates a flakier crust, why old cast iron pans add a unique depth, and why a winter tomato tastes of nothing—you can learn how to bridge the gap and systematically reclaim the authentic flavors of your culinary heritage.

This exploration will delve into the critical components that define the taste of the past. We will examine the science of fats, the legacy of cooking surfaces, the genetic truth of produce, and the psychological power of memory, providing you with the knowledge to finally make grandma’s cooking taste the way you remember.

Summary: Reclaiming the Lost Science of Heritage Cooking

- Lard vs Shortening: Why Modern Fats Ruin Vintage Pie Crusts?

- Cast Iron Seasoning: Does Old Pan Build-Up Actually Add Flavor?

- Supermarket Carrots vs Heirloom: Is the Flavor Difference Worth the Cost?

- Why Childhood Comfort Foods Never Taste As Good As You Remember?

- Convection Ovens: How to Adjust Grandma’s Temperature for Modern Appliances?

- Recipe Apps vs Vintage Cookbooks: Which Source Better Sparks Creativity?

- Why Tomatoes in January Taste Like Water (And What to Buy Instead)?

- Which 5 Essential Techniques Will Transform Your Home Cooking from Average to Restaurant Quality?

Lard vs Shortening: Why Modern Fats Ruin Vintage Pie Crusts?

The first clue in our culinary investigation often lies in the fat. Many mid-century recipes call for lard, an ingredient now largely replaced by vegetable shortening. While they may seem interchangeable, their impact on texture, particularly in pastries, is profoundly different. This isn’t a matter of opinion; it’s a matter of molecular structure. Lard possesses large, irregular fat crystals that, when worked into a dough, create distinct pockets. As the pastry bakes, these pockets melt, leaving behind air gaps that separate the dough into countless flaky, delicate layers. Shortening, by contrast, is engineered for uniformity with small, consistent crystals. This creates a tender, but much more crumbly and less flaky, texture.

The fundamental difference in composition is also key. While both are nearly pure fat, other fats like butter contain water. According to comprehensive taste tests, lard and shortening are 100% fat, while butter is 85% fat and 15% water. That water in butter turns to steam during baking, also contributing to flakiness, but in a different way than lard’s structural pockets. For recipes designed around the unique properties of lard, substituting shortening is a guaranteed way to lose the authentic texture that was central to the original dish.

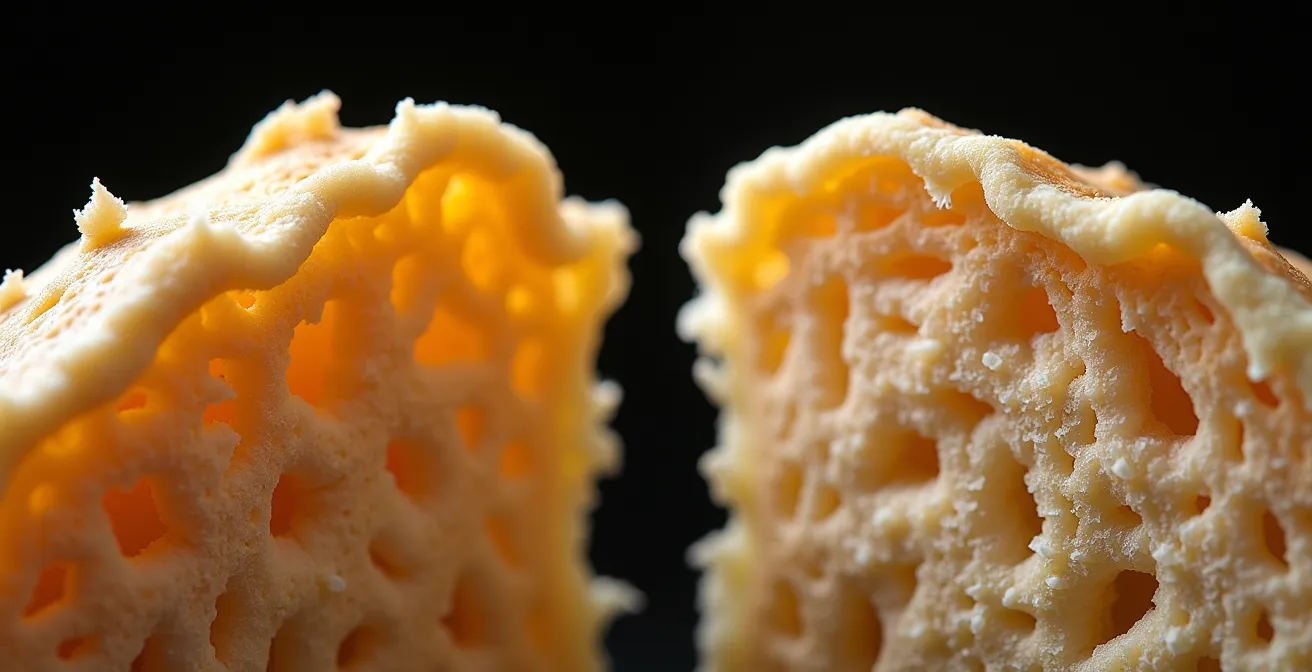

To truly understand this difference, one must look at the material science of the dough itself. The visualization below shows the distinct internal structures created by these different fats.

As the image illustrates, the lard-based dough (left) is set up for a multi-layered, shatteringly crisp result, while the shortening-based dough (right) will be more uniform and sandy. This isn’t a subtle difference; it is the very soul of a vintage pie crust. Reclaiming that taste starts with sourcing high-quality, minimally processed leaf lard, the gold standard for baking, and honoring the recipe’s original material choice.

Cast Iron Seasoning: Does Old Pan Build-Up Actually Add Flavor?

Another artifact of a grandmother’s kitchen is the heavy, black, and immaculately non-stick cast iron skillet. The common belief is that the “seasoning”—the dark coating built up over years of use—is simply layers of old food and oil that contribute a unique flavor. While there’s a kernel of truth there, the reality is far more scientific and less about leftover food particles. That dark, slick surface is not just grime; it’s a layer of polymerized oil, a food-safe, non-stick coating created through a specific chemical reaction.

Polymerization is a process where fats and oils, heated to a high temperature, transform from a liquid into a hard, solid layer that bonds directly to the metal. As culinary scientists explain, tiny fatty acid molecules link together to form long, strong polymer chains. These chains cross-link and bond with the porous surface of the iron, creating a tough, slick coating that becomes one with the pan. It’s less like a layer on top and more like a new surface that has been chemically created. This process is most effective at specific temperatures; research on cast iron seasoning science reveals that 400-500°F is the effective range for this transformation to occur properly.

So, does this seasoning add flavor? Indirectly, yes. A well-polymerized surface allows for superior heat transfer and the ability to achieve a deep, even sear without sticking. This promotes the Maillard reaction—the chemical process between amino acids and sugars that creates the complex, savory flavors of browned foods. An old pan’s seasoning doesn’t “leach” old flavors; rather, its perfectly developed surface enables the creation of *new*, more complex flavors in the food you’re cooking right now. Recreating this effect requires properly seasoning a new pan or, better yet, restoring and using a vintage one to harness its superior, time-tested surface.

Supermarket Carrots vs Heirloom: Is the Flavor Difference Worth the Cost?

You follow an old recipe for beef stew, one that calls for simple, humble carrots. Yet, the finished dish lacks the sweet, earthy depth you remember. The culprit is likely the carrots themselves. The bright orange, perfectly uniform carrots found in every supermarket today are the product of decades of breeding, not for flavor, but for yield, pest resistance, and shelf stability. They are designed to be harvested by machine, survive cross-country shipping, and look appealing under fluorescent lights for weeks. Flavor, unfortunately, has been a low priority.

This phenomenon is known as “flavor drift.” The intense, complex taste of older vegetable varieties comes from a rich array of organic compounds, including sugars and aromatic terpenoids, which give carrots their characteristic floral and pine-like notes. Heirloom varieties, which haven’t been subjected to the same industrial breeding programs, often retain much higher concentrations of these flavor compounds. They might be oddly shaped, come in various colors like purple or yellow, and have a shorter shelf life, but their flavor is exponentially more potent.

Is the difference worth the cost and effort of seeking them out at a farmers’ market? For a dish where the vegetable is a background player, perhaps not. But for a recipe where that ingredient is meant to be a star—like a carrot soup, a glazed side dish, or the foundational base of a stew—the answer is a resounding yes. Using heirloom carrots is not about being pretentious; it’s about using an ingredient that possesses the same flavor provenance as the one your grandmother used. The added sweetness and aromatic complexity they provide can be the single missing element that finally makes the recipe click into place, transforming it from a pale imitation into an authentic resurrection.

Why Childhood Comfort Foods Never Taste As Good As You Remember?

This is the question where psychology and material science intersect. There is no denying the powerful role of nostalgia in our perception of food. The context in which we first ate a dish—the sense of comfort, the presence of loved ones, the joy of a special occasion—becomes inextricably linked to its taste. This is not just a feeling; it’s a documented psychological phenomenon. As one study highlights, our emotional state has a profound impact on how we experience food.

Nostalgia for food experiences elevated comfort by strengthening social connectedness.

– Reid, C. A. et al., Food nostalgia and food comfort: the role of social connectedness

This connection is deeply personal. In fact, recent psychological research demonstrates that 24% of the total variance in how comforting a food feels is unique to the individual. This confirms that a significant part of the “magic” is, indeed, tied to our personal history and emotions. However, acknowledging this fact does not mean we should dismiss the tangible differences.

The most productive approach is to separate sensory memory from ingredient integrity. We can honor the emotional power of the memory while simultaneously conducting a culinary investigation into the physical components. It’s not a matter of “nostalgia OR different ingredients”; it’s “nostalgia AND different ingredients.” The slight sadness you feel when a dish doesn’t taste the same is real, but it can also serve as a powerful motivation. It can drive you to dig deeper, to question the modern ingredients, and to start the journey of culinary archaeology needed to restore the dish to its former glory. The goal is not to perfectly replicate a memory, which is impossible, but to honor it by recreating the dish with the same integrity it was first made with.

Convection Ovens: How to Adjust Grandma’s Temperature for Modern Appliances?

Many vintage recipes were written for conventional ovens, which cook with static, ambient heat primarily from a bottom element. Modern kitchens are often equipped with convection ovens, which use a fan to circulate hot air. This technology is more efficient, cooks faster, and promotes better browning. However, directly applying a vintage recipe’s temperature and time to a convection oven is a common recipe for failure. The circulating air accelerates cooking and can dry out baked goods or burn the exteriors of roasts before the inside is cooked.

This is a classic case of mismatched technology. Your grandmother’s instruction to “bake at 350°F for 1 hour” was calibrated for a different kind of heat environment. Ignoring this is like trying to translate a language by simply swapping words without understanding grammar. The meaning—a perfectly cooked dish—gets lost. Fortunately, the conversion is straightforward once you understand the principle. The goal is to compensate for the increased efficiency of the convection fan.

Adjusting for this difference is one of the easiest and most impactful “fixes” you can make when tackling a vintage recipe. It requires a simple, methodical approach to temperature and time. The following checklist provides a clear framework for translating old recipes for your modern appliance, ensuring you achieve the intended result without the guesswork.

Action Plan: Adjusting Vintage Recipes for a Convection Oven

- Reduce Temperature: Start by setting your convection oven 25°F (about 15°C) lower than the temperature specified in the conventional recipe.

- Shorten Cooking Time: Plan to check for doneness much earlier. A good rule of thumb is to start checking at 75% of the original recommended cooking time.

- Leverage for Roasting: Use the convection setting for roasting meats and vegetables. The dry, circulating air is ideal for creating crisp skin and deep browning.

- Disable for Delicates: Turn off the convection fan for delicate, leavened items like soufflés, custards, and cheesecakes, as the moving air can cause them to fall or cook unevenly.

- Add Humidity When Needed: For recipes that require a moist environment, like breads or custards, place a pan of hot water on a lower rack to create steam and counteract the drying effect of the fan.

Recipe Apps vs Vintage Cookbooks: Which Source Better Sparks Creativity?

In our quest to recreate heritage dishes, the source of the recipe itself is paramount. Today, we are flooded with infinite options from recipe apps and food blogs. While convenient, this digital deluge often presents a challenge. Recipes are frequently decontextualized, unvetted, and optimized for search engines rather than flavor. They lack the curation and lived experience embedded in a vintage cookbook, especially one passed down through a family.

A vintage cookbook is more than a set of instructions; it’s a historical document. It represents a curated collection of recipes that were tested, trusted, and deemed worthy of being printed and preserved. Family cookbooks are even richer, often filled with handwritten notes in the margins—”Use more ginger,” “Dad’s favorite,” “Don’t overmix!” These annotations are a direct line to the wisdom and experience of the cooks who came before us. They provide crucial context that no algorithm can offer. They are a record of the recipe’s evolution and adaptation within a specific family’s palate.

This contrast is not just about information, but about the very process of creativity and connection. The tactile experience of handling a well-loved cookbook fosters a different kind of engagement than swiping on a screen.

The image above captures this dichotomy perfectly. On one side, there is a connection to history, a physical artifact that tells a story. On the other, a clean but sterile interface. While digital tools are useful for quick lookups, the deep, creative work of understanding a recipe’s flavor provenance often begins by stepping away from the screen and engaging with the printed page. A vintage cookbook encourages a slower, more thoughtful approach, inviting you to become part of its ongoing story rather than just another user executing a program.

Why Tomatoes in January Taste Like Water (And What to Buy Instead)?

Perhaps no ingredient exemplifies the modern flavor problem more than the out-of-season tomato. A vintage recipe for a simple sauce or salad that relies on the vibrant taste of fresh tomatoes will inevitably fail when made in the winter with supermarket produce. The pale, firm, and utterly bland tomatoes available in January are a testament to the priorities of our global food system: they are bred to be picked green and hard, survive thousands of miles of shipping, and be artificially “ripened” with ethylene gas. This process gives them the color of a tomato, but none of the taste.

The rich, complex flavor of a sun-ripened tomato is a delicate chemical symphony of sugars, acids, and over a dozen key volatile compounds that create its signature aroma. This symphony can only develop when the fruit ripens on the vine, drawing nutrients from the plant. When a tomato is picked green, that process halts permanently. No amount of time on a windowsill or treatment with gas can create the flavor compounds that were never allowed to form in the first place. You are left with a watery, mealy sphere that is a tomato in appearance only.

So, what should a culinary anthropologist do when a recipe calls for an ingredient that is seasonally unavailable in its authentic form? The answer is to seek an alternative that prioritizes flavor preservation. Instead of buying the fresh-but-flavorless option, you should turn to high-quality processed tomatoes. Specifically:

- Canned Whole Tomatoes: Look for trusted brands, particularly those using San Marzano or other plum tomato varieties. These are picked and canned at the peak of ripeness, preserving their flavor integrity far better than an out-of-season “fresh” tomato.

- Tomato Passata or Purée: These are uncooked, strained tomatoes, offering a pure, fresh-tasting base that is excellent for sauces. They provide the flavor without the fibrous texture of a poor-quality fresh tomato.

- Sun-Dried Tomatoes: For an intense, concentrated burst of umami and sweetness, sun-dried tomatoes (especially those packed in oil) can add the depth that a winter tomato lacks, though their texture makes them unsuitable for all applications.

By choosing the preserved peak-season ingredient over the cosmetically fresh one, you are making a choice that honors the recipe’s original intent: to taste like a tomato.

Key Takeaways

- Ingredient Integrity is Paramount: The molecular structure of fats (lard vs. shortening) and the genetics of produce (heirloom vs. industrial) have a greater impact on the final dish than most cooks realize.

- Your Tools Have Changed: Modern convection ovens and pristine non-stick pans do not behave like the conventional ovens and seasoned cast iron for which vintage recipes were written. Adjustment is necessary.

- It’s Not Just Nostalgia: While psychology plays a role, the “flavor drift” in our food supply is a real, measurable phenomenon. Your palate is likely detecting a genuine difference.

Which 5 Essential Techniques Will Transform Your Home Cooking from Average to Restaurant Quality?

Successfully recreating heritage recipes is not just about using the right ingredients; it’s also about mastering the foundational techniques that were second nature to previous generations of home cooks. Many of these skills have been lost in the age of convenience, yet they are the bedrock of profound flavor development. By reintegrating these five essential techniques into your cooking, you can bridge the final gap between an average meal and a restaurant-quality dish that truly honors its origins.

These methods are not complex, but they require patience and attention. They are the “how” that unlocks the full potential of the “what.” Mastering them is the final step in your journey as a culinary anthropologist, moving from simply following a recipe to truly understanding and controlling the creation of flavor in your kitchen.

- Achieving a Proper Sear: This is more than just “browning.” A true sear involves cooking meat or vegetables in a very hot pan (like well-seasoned cast iron) with enough space so they are not steaming. This triggers the Maillard reaction, creating hundreds of new aroma and flavor compounds that provide a deep, savory complexity that cannot be achieved otherwise.

- Building a Fond: After searing, you’ll see browned bits stuck to the bottom of the pan. This is the “fond,” and it is concentrated flavor gold. Never wash it away. Instead, “deglaze” the pan by adding a liquid (wine, stock, even water) and scraping the bits up. This incorporates that intense flavor into your sauce, stew, or gravy.

- Mastering Acidity: A common reason a rich, savory dish tastes “flat” or “heavy” is a lack of acidity. A splash of vinegar, a squeeze of lemon juice, or a spoonful of wine added at the end of cooking can brighten and balance the entire dish, making all the other flavors pop. Grandmothers did this instinctively.

- Creating a Stable Emulsion: For sauces and vinaigrettes, understanding how to create an emulsion—the stable mixture of fat and water—is critical. This means adding oil slowly while whisking vigorously to break it into tiny droplets that can remain suspended in the liquid, creating a creamy, cohesive texture instead of a broken, oily mess.

- The Art of Resting: This is perhaps the most crucial and most ignored step for cooked meats. After removing a roast or steak from the heat, you must let it rest for 5-15 minutes. This allows the muscle fibers to relax and reabsorb their juices. Slicing into it immediately will cause all that flavorful moisture to spill out onto the cutting board, resulting in dry, less-tasty meat.

Begin your own culinary archaeology today. Re-examine your family’s recipes not as mere instructions, but as historical documents rich with clues. By focusing on ingredient integrity, understanding the science of your tools, and mastering foundational techniques, you can move beyond imitation and rediscover the true, authentic taste of your heritage.