To view mole as a ‘chocolate sauce’ is to fundamentally misunderstand it. Mole is not a single recipe but a culinary philosophy of balance, where dozens of ingredients are not a complication but an essential symphony. The chocolate is a minor player in a complex orchestra of chiles, nuts, and spices, each chosen for a specific chemical and historical purpose that defines the soul of authentic Mexican cuisine.

When most people hear the word “mole,” their mind often jumps to one place: a rich, dark, vaguely sweet sauce with a hint of chocolate, served over chicken. This common perception, largely shaped by simplified versions found outside of Mexico, does a profound disservice to one of the world’s most complex and historically significant culinary creations. The truth is, mole is not one sauce. It is a universe of sauces, a testament to centuries of regional history, agricultural diversity, and the alchemical genius of Mexican kitchens. To ask if chocolate is a gimmick is to miss the point entirely.

The real question is not *what* is in mole, but *why* it is there. Why the toasted nuts? Why the specific blend of dried chiles? Why the whisper of canela or the hint of anise? The complexity is not a bug; it is the entire feature. It represents a pre-Hispanic tradition of layered, intricate flavors, later blended with Old World ingredients. This article moves beyond the platitudes to explore the foundational principles of Mexican cuisine, using specific, often misunderstood, ingredients and techniques as a lens. We will deconstruct the ‘why’ behind the choices a true cocinero or cocinera makes, from the herbs in their beans to the tortilla that cradles their taco.

This journey will reveal that authenticity in Mexican food is not about rigid rules, but about a deep understanding of how ingredients work together. It’s a philosophy of balance, transformation, and terroir. By the end, you will not just understand mole better; you will have a new appreciation for the profound depth and intelligence of Mexico’s culinary heritage.

To guide this exploration, we will delve into specific questions that reveal the core principles of authentic Mexican cooking. The following sections break down these concepts, from foundational ingredients to regional distinctions.

Summary: Deconstructing the Pillars of Authentic Mexican Cuisine

- What is Epazote and Why Is It Essential for Bean Digestion?

- Oaxaca vs Mozzarella: Are They Interchangeable in Quesadillas?

- Cheek or Chuck: Which Cut Yields the Most Tender Barbacoa?

- Cumin Overload: How to Spot the Difference Between Tex-Mex and Interior Mexican?

- Lime or Vinegar: Which Acid Preserves Salsa Fresca Longer?

- Gochujang and Miso: Which Panty Staples Offer the Most Versatility?

- Ancho vs Poblano: How Drying Changes the Flavor Profile Completely?

- Corn vs Flour: Which Tortilla is Authentically Paired with Which Taco Filling?

What is Epazote and Why Is It Essential for Bean Digestion?

The philosophy of Mexican cooking often involves ingredients that serve a dual purpose: flavor and function. Epazote is a prime example of this principle. To an outsider, it’s a pungent, sharp herb, but within the tradition, it is the indispensable partner to beans. Its flavor is assertive, with notes of anise, mint, and even creosote, but its primary role for centuries has been medicinal. The name itself comes from the Nahuatl words *epazōtl*, meaning “skunk sweat,” a testament to its powerful aroma.

The herb’s most celebrated function is as a carminative, an agent that helps to prevent and expel intestinal gas. This is why a sprig of epazote is traditionally tossed into a simmering pot of black beans, pinto beans, or lentils. It’s not just seasoning; it’s a form of ancestral wisdom designed to make a foundational food more digestible. Furthermore, its functional properties extend beyond this; studies have shown its effectiveness as a natural vermifuge. For instance, a 2015 clinical pilot study showed that an epazote infusion had significant antiparasitic effects. This illustrates that ingredients are chosen for a holistic purpose, a concept central to understanding complex dishes like mole, where spices contribute more than just taste.

Case Study: The Traditional Use of Epazote in Frijoles de la Olla

In countless Mexican households, the preparation of *frijoles de la olla* (pot beans) is a weekly ritual. The classic pairing is with black beans, pinto beans, or lentils. Drop a sprig into the simmering pot, and suddenly the beans feel lighter on the stomach. Anyone who eats beans regularly knows the potential for discomfort. For centuries, before the advent of modern digestive aids, epazote was tossed into the pot, not just as seasoning but as functional support. This practice showcases a deep-seated understanding of food as both nourishment and medicine.

Oaxaca vs Mozzarella: Are They Interchangeable in Quesadillas?

The question of substituting Oaxaca cheese with mozzarella in a quesadilla cuts to the heart of what makes an ingredient authentic: it’s not just about taste, but about texture and behavior. Both are stretched-curd cheeses, a technique known as *pasta filata*, but their structural differences create vastly different eating experiences. Mozzarella, particularly the low-moisture variety, melts into a relatively uniform, homogenous layer. It’s good, but it’s not the goal of a true Mexican quesadilla.

Oaxaca cheese, on the other hand, is a masterpiece of texture. It is formed into a long rope and wound into a ball, resembling a ball of yarn. This process isn’t just for show; it aligns the protein strands in the cheese. When melted, Oaxaca cheese doesn’t dissolve into a puddle. Instead, it pulls apart in long, distinct, and satisfying strings. This textural quality is paramount. The science confirms this; research on pasta filata cheeses shows that the unique stretching process of Oaxaca cheese results in a highly organized protein network that gives it its characteristic stringiness when heated. While mozzarella provides flavor and melt, only Oaxaca cheese delivers the signature “pull” that defines an authentic quesadilla experience.

This is why they are not truly interchangeable. Using mozzarella might create a tasty melted cheese pocket, but it misses the specific textural joy that the Oaxacan preparation method was designed to produce. It highlights a key theme: in Mexican cuisine, the *how* an ingredient is made is as important as the *what*.

Cheek or Chuck: Which Cut Yields the Most Tender Barbacoa?

Barbacoa is not a flavor; it is a cooking method, traditionally involving slow-cooking meat in an underground oven covered with maguey leaves. The choice of meat is therefore critical, and the debate between beef cheek (*cachete*) and chuck roast reveals a deep understanding of meat science. While both can be used, they yield different types of “tender.”

Beef cheek is the traditional, superior choice for authentic barbacoa. This muscle is used constantly for chewing, making it tough but also incredibly rich in collagen. During the long, slow, steamy cooking process of barbacoa, this collagen breaks down into luscious, unctuous gelatin. The result is a meat that is not just soft, but incredibly moist, silky, and rich in mouthfeel. It shreds effortlessly and carries an intense, beefy flavor that is unparalleled. This is the gold standard for taco de barbacoa.

Chuck roast, a cut from the shoulder, is more familiar to many. It is well-marbled with fat, which also renders during slow cooking to produce a tender result. However, it lacks the extreme collagen content of the cheek. Chuck will become soft and shreddable, but it will never achieve the same level of gelatinous richness and succulence. It produces a drier, more stringy texture in comparison. So, while chuck can make a delicious pot roast, cheek is the cut that is structurally perfect for the low-and-slow steam environment of barbacoa. The choice is a deliberate one, made to maximize the transformation of a tough, hard-working muscle into something sublime.

Cumin Overload: How to Spot the Difference Between Tex-Mex and Interior Mexican?

One of the quickest ways to distinguish Americanized Tex-Mex from the cuisines of Interior Mexico is to follow your nose. If a dish is dominated by the single, dusty, earthy note of cumin, you are likely in Tex-Mex territory. While cumin (*comino*) is used in Mexico, it’s typically a subtle background player in a much larger orchestra of spices. In Tex-Mex cooking, it was elevated to a primary flavor, becoming a convenient shorthand for “Mexican flavor.”

Interior Mexican cuisine, by contrast, relies on a vast and nuanced palette of spices tailored to each specific dish and region. A mole from Oaxaca might rely on the smoky depth of pasilla chiles, the warmth of canela (true cinnamon), and the licorice notes of hoja santa. A cochinita pibil from the Yucatán gets its soul from bitter orange and the earthy, peppery flavor of achiote (annatto seed). Spices like allspice, cloves, and Mexican oregano are used with precision and restraint. The goal is not a monolithic “taco seasoning” flavor but a complex, layered aroma where no single spice screams for attention. This is the “Ingredient Symphony” in practice.

The “cumin overload” in Tex-Mex is a product of simplification, designed for broad appeal and easy replication. It’s a single loud instrument versus a finely tuned orchestra. Recognizing this difference is the first step toward appreciating the true diversity and sophistication of Mexico’s regional cuisines.

Your Action Plan: Auditing a Recipe for Mexican Authenticity

- Analyze the Spices: Does the recipe rely heavily on cumin and chili powder, or does it call for a variety of specific whole or ground spices like allspice, canela, or cloves?

- Examine the Chiles: Does it list “chili powder,” or does it demand specific dried chiles like ancho, guajillo, or chipotle, and specify toasting or rehydrating them?

- Check the Acid: Is it using distilled white vinegar for a fresh salsa, or is it calling for fresh lime or even bitter orange juice?

- Assess the Herbs: Is cilantro used as a simple garnish, or does the recipe incorporate other herbs like epazote or hoja santa for deeper, functional flavor?

- Look at the Fat: Does the recipe use a neutral vegetable oil, or does it call for lard (*manteca*), which provides a specific flavor and texture foundational to many traditional dishes?

–

Lime or Vinegar: Which Acid Preserves Salsa Fresca Longer?

The choice of acid in a salsa is another subtle but telling detail. In the context of *salsa fresca*—also known as *pico de gallo*—the choice is always fresh lime juice. The goal of this preparation is not preservation but immediate, vibrant flavor. It is meant to be made and consumed within hours. The bright, floral, and slightly sweet notes of fresh lime juice are essential to elevating the flavors of the fresh tomato, onion, and cilantro. It’s a flavor catalyst, not a preservative.

From a chemical standpoint, vinegar is a more effective preservative. Most vinegars have a lower pH (are more acidic) than lime juice, and acetic acid (the acid in vinegar) is generally more hostile to microbial growth than citric acid (the acid in limes). This is why vinegar is the acid of choice for pickled jalapeños (*escabeche*) and jarred, shelf-stable salsas. Its sharp, pungent flavor profile is also better suited to cooked and preserved preparations.

Therefore, while vinegar will make a salsa last longer in the refrigerator, it would be an inauthentic and overpowering choice for a classic salsa fresca. Using it would sacrifice the fresh, delicate balance of flavors that defines the dish. The choice isn’t about which is “better,” but which is right for the intended purpose. One is for immediate brightness, the other for long-term stability. This demonstrates the intentionality behind even the smallest ingredient choices in the Mexican kitchen.

Gochujang and Miso: Which Panty Staples Offer the Most Versatility?

In many modern kitchens, Asian pantry staples like gochujang and miso are rightly celebrated for their versatility. Miso provides a profound, salty umami depth from fermented soybeans, capable of enriching everything from soup to marinades. Gochujang, a fermented Korean chili paste, offers a complex trifecta of sweet, savory, and spicy. Their power comes from fermentation, a biological process that creates deep, complex flavors over time.

To understand the versatility of the Mexican pantry, one must look to a different kind of alchemy: the alchemy of the *comal* and the fire. The Mexican equivalent of this versatile staple is not found in fermentation, but in the complex pastes created from dried chiles, nuts, seeds, and spices. Consider a jar of concentrated mole base or an adobo paste made from toasted and rehydrated ancho and guajillo chiles. This base is not just “spicy.” It carries the smoky, fruity, and earthy notes developed through toasting and roasting—a process of caramelization and the Maillard reaction that creates hundreds of new flavor compounds.

While miso adds umami, a chile paste adds a landscape of flavor. It can be thinned with broth for a sauce, used as a marinade for meats like al pastor, stirred into soups for depth, or blended with fat to season tamal masa. Its versatility comes not from the singular magic of fermentation, but from the symphony of dozens of ingredients, each transformed by fire. It is a different culinary philosophy, one of layering and building complexity through heat and transformation, rather than time and microbes.

Ancho vs Poblano: How Drying Changes the Flavor Profile Completely?

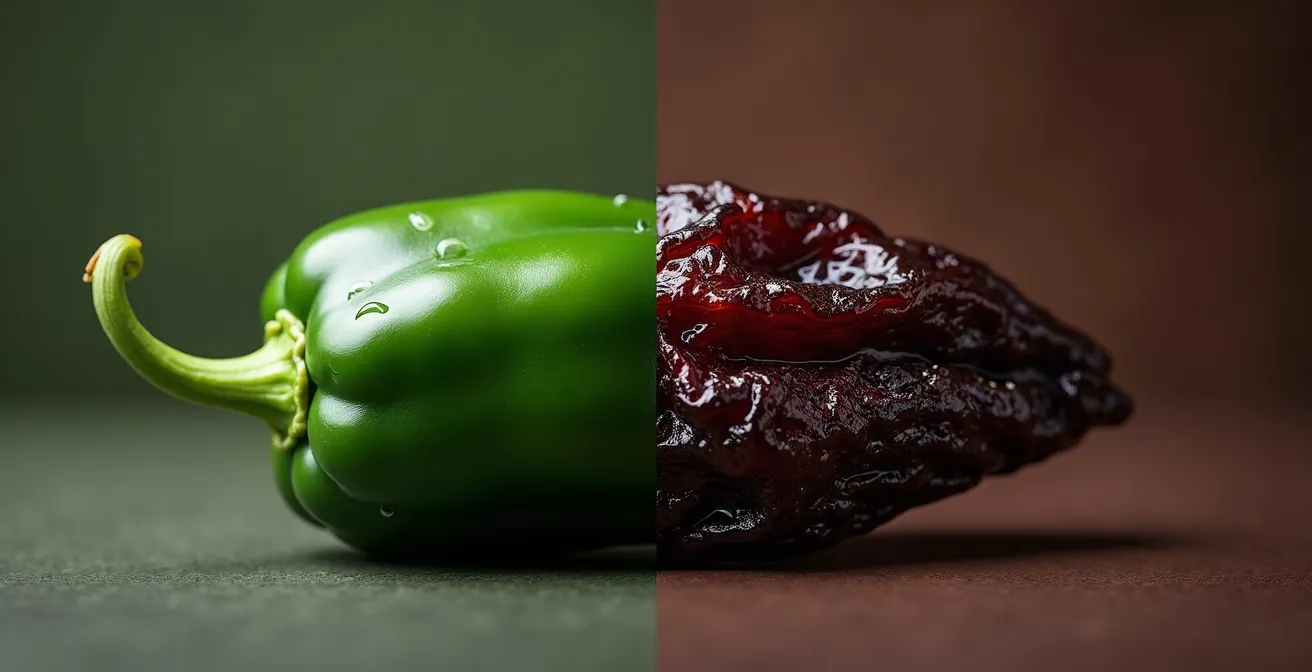

There is no better illustration of flavor alchemy in Mexican cuisine than the transformation of a fresh poblano pepper into a dried ancho chile. They are the same fruit, yet they are two entirely different worlds of flavor. The poblano is a mild, green, and vegetal pepper, prized for its use in dishes like chiles rellenos, where its sturdy walls and gentle flavor provide a perfect vessel for cheese or meat.

When a mature, red poblano is dried, it becomes an ancho. This process of dehydration does more than just remove water; it triggers a cascade of chemical changes. The sugars in the pepper become concentrated and begin to caramelize, and the Maillard reaction between sugars and amino acids creates a host of new, complex flavor compounds. The vegetal, green notes of the poblano disappear, replaced by a rich, complex profile of fruit, smoke, and earth. The resulting ancho chile has notes of dried plum, raisin, coffee, and tobacco. Its heat is also gentle; for example, ancho chiles measure approximately 1,000-1,500 SHU on the Scoville Scale, making them more about flavor depth than intense spice.

This transformation is the very soul of mole and many other Mexican sauces. The cuisine is built upon the understanding that drying a chile is not just for preservation, but for the creation of entirely new flavors. You cannot replicate the taste of an ancho by simply using a poblano. One is a starting point; the other is a destination, reached through the transformative power of time and sun.

Key Takeaways

- Authentic Mexican cooking is a philosophy of balance, where ingredients are chosen for both flavor and function.

- The transformation of ingredients through processes like drying and toasting is fundamental to creating deep, complex flavors that cannot be substituted.

- Regional differences are not arbitrary but are deeply tied to local history, agriculture, and specific culinary techniques.

Corn vs Flour: Which Tortilla is Authentically Paired with Which Taco Filling?

The choice between a corn and flour tortilla is not a matter of preference but of history and geography. It is the final piece of the puzzle that grounds a taco in its specific regional identity. The foundation of all Mexican cuisine is maize (corn). For thousands of years, corn has been the grain of life in Mesoamerica, and the corn tortilla, made from masa that has undergone nixtamalization, is its most iconic form. This process of soaking corn in an alkaline solution unlocks nutrients and creates its signature pliable texture and earthy aroma. In the central and southern regions of Mexico—the historical heartland of maize—the corn tortilla is the undisputed king. Fillings like *al pastor* with its Mexico City origins or *carnitas* from Michoacán belong on a corn tortilla.

The flour tortilla, on the other hand, is a product of Northern Mexico. When the Spanish arrived, they brought wheat, which thrived in the arid, cooler climate of the north. Flour tortillas became a staple in states like Sonora and Chihuahua. They are traditionally made with lard, giving them a soft, flaky, and rich character that is distinct from the chewy, rustic corn tortilla. These larger, sturdier tortillas are the authentic pairing for northern dishes like *carne asada* or barbacoa, which have strong roots in the ranching culture of the region.

Pairing the wrong tortilla with a filling is like serving a fine Burgundy in a water glass—it works, but it misses the entire point of the pairing. The tortilla is not just a wrapper; it is the culinary foundation of the taco, and its choice is deeply rooted in the concept of regional terroir.

By appreciating these details, from the type of chile to the tortilla it’s served on, you move beyond the surface and begin to truly understand the depth, history, and genius of Mexican food. The next step is to start exploring these concepts in your own kitchen.